My daughter is crying that her piano lessons make no sense. It’s been all of about a week, and she’s ready to give up.

Sharps, flats, finger positions, counting the beats. It’s difficult.

Instead she wants to learn violin.

“How will that be any easier?” I ask.

But she’s too frustrated to have a rational conversation, and has no experience with violin to give an answer.

As parents, my wife and I try to impart our wisdom and knowledge to our kids. And I don’t think we’ll stop trying — everyone likes to give unsolicited advice.

“Practice and patience,” I suggest. “A seed doesn’t become a tree overnight. Remember when you wanted to do cartwheels? or ride a bike? Learning those things took time, frustration, and failure. Until you got it right.”

But people, kids and adults alike, don’t learn grit from a pep talk. You don’t automatically adopt new behaviors because someone suggested them.

You change behaviors because you learn from experience and observation what works and what doesn’t work for you, the people you know, and (with time) the books you read and the television you watch.

You change behaviors when the pain, real or imagined or expected, is worse than the cure.

Some people may never find a cure, and continue to live in pain.

Advice from others falls on deaf ears, because change is difficult and they don’t have the experience to value someone’s solution (and besides, they know all the reasons it won’t work).

Or accepting that solution goes against the story they tell themselves about who they are and how the world works.

I tell myself the story that I am open to new ideas, new ways to do things, and the world is much larger than what I understand.

And, I believe it. But it usually takes the experience to try and prove the new idea to myself before I commit to it. And even then, sometimes…

First Idea Wins

You learn best from failure. Test your idea, fail, learn, adapt.

That’s how it should go, at least. It’s what you expect from others, after all.

And if the failure has no real consequence, you may not learn anything.

Instead, the first idea that we accept… factual or not… often becomes part of the story we tell ourselves, and is the idea we stick with:

I’ll never vote for that party, they’re obviously ___-ist.

Your story wins, even if it’s not true.

Ego investment is when we invest our sense of self in our ideas.

When those ideas are attacked, it feels like a personal attack. In response, we justify that position, we dig in deeper, we fight back, we refuse to change because I’m smart and obviously this is the way things should work.

At home my wife and have different ideas on our appliances:

- Clothes drier: Timed Dry, or Moisture Auto-Sensing?

- Dish washer: Power Scrub, which may use more electricity (no data), or Regular Wash, which is 10 minutes longer (so maybe that uses more electricity)?

And as much as we’ve tried to convince the other that…

my dear, your way is wrong, try it my way

…for 10 years neither of us has adopted the other way. There’s no real pain involved, so nothing to remedy. And so we keep changing the settings on the appliances, wondering why the other is stuck on doing things wrong.

For Example

Children learn through imitation how to interact with their world, and through the resulting experience.

I can offer my help and suggestions, but mostly the kids are not interested. They didn’t ask and I obviously don’t understand what they’re going through.

It’s my stories and behaviors that seem to stick with them, the conversations that aren’t related to their problems, that impact my kids.

There’s no investment when Dad makes a mistake or describes why he picked one thing or another. But they get to observe the behavior and reaction.

And that requires a level of humility to discuss my mistakes and failures, many of which I probably forget (because our brains rewrite the world to make us heroes).

I can’t force my daughter to be interested in piano. I can’t force her to have more grit.

I can live by example, to attempt to be worthy of imitation.

I can fall, fail, and make mistakes. Take a break, come back again. Push myself a bit more. Ask questions and seek advice. Practice.

And I can do that in front of my kids. I should do that in front of my kids.

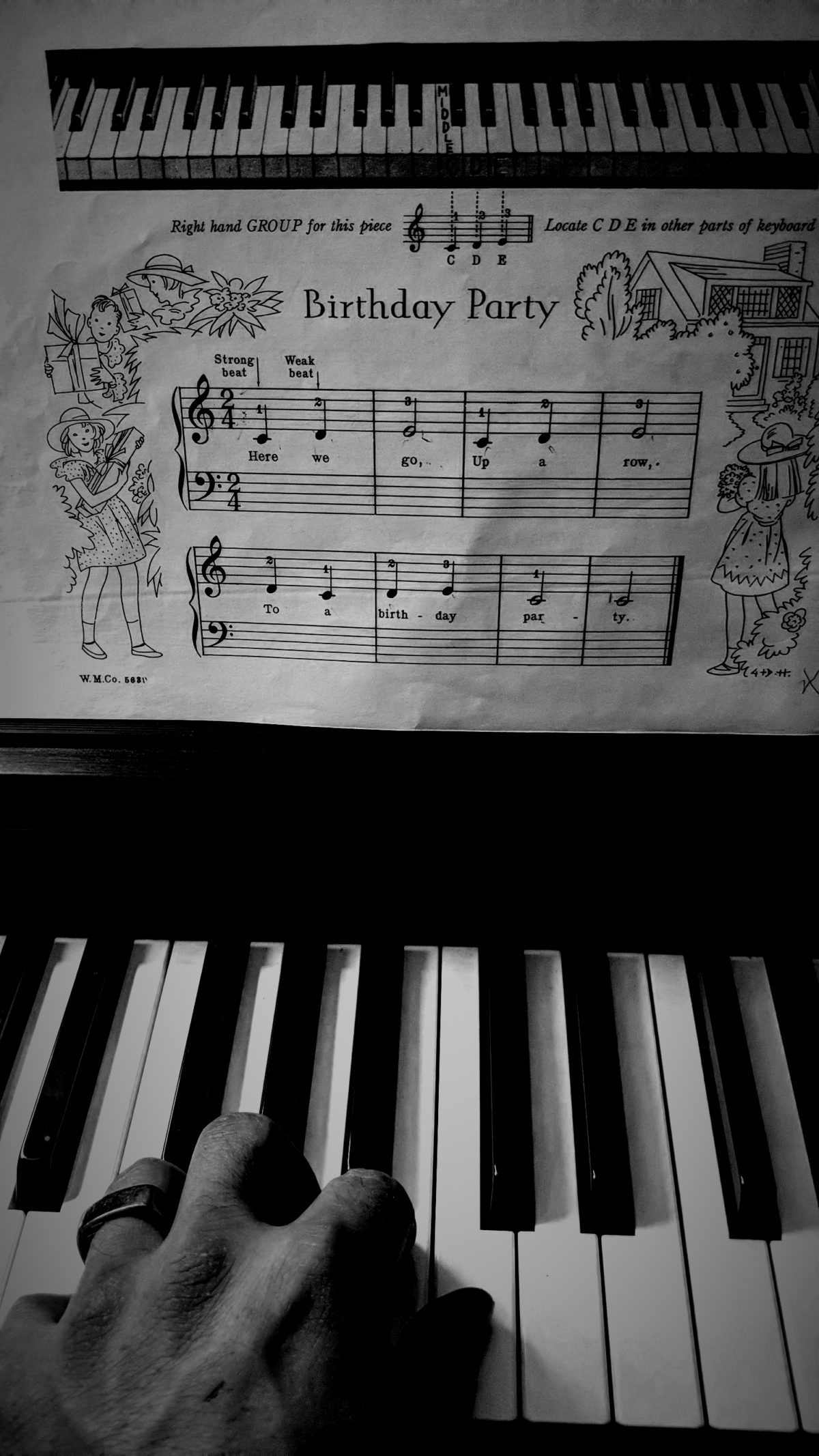

I don’t know how to play the piano, yet. So at age 41, I am now starting at the beginning.

Sharps, flats, finger positions, counting the beats. It’s difficult.